For some years now, I’ve been wishing I could smack American culture as a whole upside the head with this week’s book. Fifty Shades of Twilight is only the latest iteration of the problem’s symptoms. James T. Kirk, James Bond, Jim West, Robert Hogan—I could go on and on listing examples of the notion that a hero will have girls throwing themselves at his feet every week, with manhood defined not by virtue but by virility. But the problem is even older and deeper than that. Romeo and Juliet, Abelard and Heloise, Tristan and Isolde, Lancelot and Guinevere… they all imply that romantic love is the highest and best form of love, that such a feeling is worth sacrificing even Camelot for the sake of the beloved, and that life bereft of such love is not worth living. Now society’s reached a point where it seems a large number of people can’t conceive of any form of love that isn’t inherently sexual.

And it’s all a thrice-accurséd lie.

In The Four Loves, C. S. Lewis spends one chapter each examining the four Greek words for love in ascending order of importance. Eros, romantic or sexual love, may need the least explanation as a concept; what needs more explanation is the idea that eros is in fact the lowest of the loves, partly because of the ease with which it becomes the vice of lust. Eros is a passion, an emotion, and as such belongs to the lower powers of the soul. Moreover, Lewis notes, eros drives a couple to turn inward, looking only at each other and shutting out anything else—potentially up to and including God.

In The Four Loves, C. S. Lewis spends one chapter each examining the four Greek words for love in ascending order of importance. Eros, romantic or sexual love, may need the least explanation as a concept; what needs more explanation is the idea that eros is in fact the lowest of the loves, partly because of the ease with which it becomes the vice of lust. Eros is a passion, an emotion, and as such belongs to the lower powers of the soul. Moreover, Lewis notes, eros drives a couple to turn inward, looking only at each other and shutting out anything else—potentially up to and including God.

Lewis gives the second place in this hierarchy to storge, affection. Storge is a much more general term than eros because it includes many more kinds of relationships: parents and children, pets and owners, heroes and the villains they love to hate. Even the way we feel about our favorite foods, books, music, or films is storge. But this love, too, is only a passion.

Third, Lewis explores philos, friendship or brotherly love. One can hear echoes in this chapter of Lewis’ own great friendships, especially with Tolkien and the Inklings. Friends may come together over a shared interest, he states, but eventually that interest becomes only incidental to the friendship. Good friends may spend hours talking and have a grand time but not necessarily remember what was said after the conversation is over; what actually mattered was spending time together. And unlike eros, philos is focused outward, open to bringing more friends into the circle. Whereas lovers stand across from each other, looking at each other, friends stand side by side looking at something else. Yet even friendship is a passion, a feeling that can fade.

Last and greatest, therefore, is agape, the word used in the New Testament to describe the unconditional, sacrificial love of God. Its chief characteristic is desiring good for the other person, regardless of what that means for the self. Far from being a passion, agape is an act of will, one of the higher powers of the soul, and doesn’t depend on any kind of emotion or anything inherently likeable about the other person; as such, it’s the only form of love considered a virtue. When the Bible commands Christians to love their neighbors and their enemies—generally, as G. K. Chesterton once quipped, because they’re the same people—the command refers to agape. And “Greater [agape] hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13).

A healthy romantic relationship, of course, will exhibit all of these kinds of love. But even when the passions fade in the face of hardship or age or hurt feelings, agape is the glue that can hold the relationship together until the other emotions can be restored. While writing The Four Loves, Lewis himself experienced the importance of agape in his relationship with Joy Davidman, whom he married at her hospital bedside when she was believed to be dying of cancer. Though she miraculously went into remission for several years and the marriage was very happy during that time, he didn’t stop loving her when the cancer returned and proved fatal—and when it comes to love stories, I’d stack either version of Shadowlands up against Fifty Shades any day.

Like a number of his other books, including

Like a number of his other books, including

As I write this morning, the baseball world is still in shock over the sudden death of 22-year-old Cardinals rookie

As I write this morning, the baseball world is still in shock over the sudden death of 22-year-old Cardinals rookie

The problem Swift identifies in “A Modest Proposal” was very real. At the time, the Irish were suffering heavily under English rule, and soul-crushing poverty was rampant in Ireland. But knowing how often straightforward argument had already failed to convince the absentee English landlords to change their ways, Swift turns the form on its ear at the beginning of the solution section and makes a statement so outlandish, so outrageous, so over-the-top that only Hannibal Lecter could approve:

The problem Swift identifies in “A Modest Proposal” was very real. At the time, the Irish were suffering heavily under English rule, and soul-crushing poverty was rampant in Ireland. But knowing how often straightforward argument had already failed to convince the absentee English landlords to change their ways, Swift turns the form on its ear at the beginning of the solution section and makes a statement so outlandish, so outrageous, so over-the-top that only Hannibal Lecter could approve: And then, in the reply to objections, Swift springs his trap. “Therefore let no man talk to me of other expedients,” he says—and proceeds to list his real recommendations, ranging from taxes on absentee landlords to what William Wilberforce would later call “the reformation of manners.” Swift then closes this section by repeating his admonition that no one should offer such options “till he hath at least some glimpse of hope, that there will ever be some hearty and sincere attempt to put them into practice.” By pretending to dismiss these ideas as wishful thinking and renewing his recommendation of a more drastic and barbaric solution, Swift prompts the reader to reconsider how quickly the aristocracy had brushed aside truly ethical and humane reforms as folly.

And then, in the reply to objections, Swift springs his trap. “Therefore let no man talk to me of other expedients,” he says—and proceeds to list his real recommendations, ranging from taxes on absentee landlords to what William Wilberforce would later call “the reformation of manners.” Swift then closes this section by repeating his admonition that no one should offer such options “till he hath at least some glimpse of hope, that there will ever be some hearty and sincere attempt to put them into practice.” By pretending to dismiss these ideas as wishful thinking and renewing his recommendation of a more drastic and barbaric solution, Swift prompts the reader to reconsider how quickly the aristocracy had brushed aside truly ethical and humane reforms as folly. convention prevents him from changing the most important points of the plot, Chaucer rejects the tendency of every other version—later including

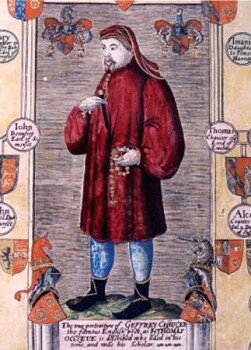

convention prevents him from changing the most important points of the plot, Chaucer rejects the tendency of every other version—later including  Chaucer hints at this ruthlessness toward the end of Book II, when Pandarus takes Criseyde a letter from Troilus. She tries to refuse it, but he brushes off her objections and stuffs the letter down the front of her dress. When she succumbs to his insistence that she reply, Troilus pressures Pandarus into pushing the courtship even further… until at last, one dark and stormy night, Pandarus all but throws them into bed together and sleeps outside the door to ensure the tryst is both secret and successful. Criseyde curses Pandarus the next morning for putting her in this position, but she has finally convinced herself that she’s in love with Troilus.

Chaucer hints at this ruthlessness toward the end of Book II, when Pandarus takes Criseyde a letter from Troilus. She tries to refuse it, but he brushes off her objections and stuffs the letter down the front of her dress. When she succumbs to his insistence that she reply, Troilus pressures Pandarus into pushing the courtship even further… until at last, one dark and stormy night, Pandarus all but throws them into bed together and sleeps outside the door to ensure the tryst is both secret and successful. Criseyde curses Pandarus the next morning for putting her in this position, but she has finally convinced herself that she’s in love with Troilus. But Criseyde’s father prevents her from leaving camp to meet Troilus, and Diomedes decides to win her love for himself, offering her friendship and service at first. He doesn’t press when she tells him she can’t consider accepting a Greek lover, although he does continue to court her. And while Chaucer argues that she’s never really in love with Diomedes, he has to concede that she does eventually begin to favor Diomedes with gifts that had belonged to Troilus.

But Criseyde’s father prevents her from leaving camp to meet Troilus, and Diomedes decides to win her love for himself, offering her friendship and service at first. He doesn’t press when she tells him she can’t consider accepting a Greek lover, although he does continue to court her. And while Chaucer argues that she’s never really in love with Diomedes, he has to concede that she does eventually begin to favor Diomedes with gifts that had belonged to Troilus. Coleridge and Charles Lamb revived his reputation among the Romantics. Contemporary Thomas Carew went so far as to claim in an elegy that English poetry had died with Donne because no other poet would dare achieve the same level of originality and creativity. Nor was Donne renowned only for his poetry. After he was named a Royal Chaplain and later Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, he became known as one of the greatest preachers of his day. And

Coleridge and Charles Lamb revived his reputation among the Romantics. Contemporary Thomas Carew went so far as to claim in an elegy that English poetry had died with Donne because no other poet would dare achieve the same level of originality and creativity. Nor was Donne renowned only for his poetry. After he was named a Royal Chaplain and later Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, he became known as one of the greatest preachers of his day. And