From my first post at Smash Cut Culture, I’ve been reviewing movies and contributing my thoughts on film-making, narrative storytelling, and media culture.

Part of the joy of writing for this platform is that I get to (try to) put aside my personal biases and look at media purely from the perspective of artistic critique. It would be pointlessly solipsistic to write, “I like this,” or, “I hate that,” and have that lazy and defenseless opinion stand in for something worth reading. After all, the goal is to actually think about a work of art as objectively as possible and then discuss its quality and value (or lack thereof) based on its own merits.

Unfortunately, all this means that artistic critique is really not a good job for people who need to be liked by everyone, and it’s also not a job for people who can’t separate themselves; their own personal tastes; or their pre-conceived biases from the subject matter at hand.

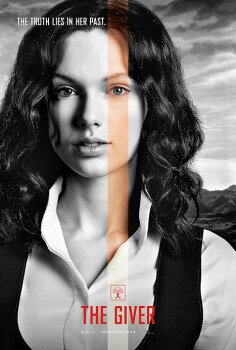

I’ve recently written scathing reviews of the films “Snowpiercer” and “The Giver”.

These movies both feature strong (some might say preachy), yet largely opposing, political messages. “The Giver” warns of the totalitarianism borne out of the desire to perfect and homogenize society through well-meaning but heavy-handed government. “Snowpiercer” attempts to be a parable about environmental destruction and wealth inequality as a consequence of unchecked private sector greed.

I am biased towards one of these perspectives and could easily argue that we are already moving toward the future it depicts, and that the other worldview is critically flawed and built on a systemic rejection of reality, but I won’t go into which is which, as that would actually step on the broader point I want to make here.

I am biased towards one of these perspectives and could easily argue that we are already moving toward the future it depicts, and that the other worldview is critically flawed and built on a systemic rejection of reality, but I won’t go into which is which, as that would actually step on the broader point I want to make here.

If you judge a movie based on how much you agree or disagree with its message or how superficially you like or dislike its themes, you’re doing film criticism wrong.

If I allowed my philosophical or political views to sway my ability to objectively assess the quality of the films I write about, I would have only written one bad review. But that would also have done a disservice to everyone who reads my commentary, and I would be proving myself to be horribly unreliable as a critic.

Film-making is a multidisciplinary art-form and doesn’t usually live or die based solely on the message or ideology expressed in the movie. And it shouldn’t. A movie with a bad message can be a well-made film (see also: Sergei Eisenstein’s “Battleship Potemkin”). Likewise, a movie with a great message can be awful.

“The Giver”, for instance, was preview screened for many conservative and libertarian organizations, as they were (correctly) assumed to be friendly audiences for the anti-government themes in the movie. While proper reviews were embargoed for a few weeks after the screening, attendees were encouraged to write “think pieces” about the messages and the political content.

Here’s one example from FreedomWorks’ Logan Albright, titled “‘The Giver’ Brings New Life to Themes of Liberty”:

“The Giver is that rare film that successfully merges conservative and libertarian themes with superior craftsmanship and genuine entertainment. The celebration of individual differences, of emotion, of life, of freedom, and of the general messiness that is the human condition strikes deep, as we instinctively reject the placid, yet soulless, sameness of a society controlled from the top down.

…

The underlying message is universal enough to appeal to everyone.”

Alas, the film did not appeal to everyone.

It bombed at the box-office, earning less than $13 million dollars on its opening weekend and scoring a paltry 32% “fresh” critics’ rating at Rotten Tomatoes. The failure of “The Giver” was even a bit predictable given who made it. Walden Media has amassed a track record of adapting books to create major flops. But I would argue that it didn’t appeal to everyone because first and foremost, it was a terrible film.

In my experience, non-liberal cultural critics spend a lot of time complaining about how few works of art, particularly film & television productions, express ideas that align with their worldviews. And they’re right. Most producers and artists in Hollywood don’t really like many ideas that fall outside the narrow confines of cocktail party-progressivism. Movies with conservative or even libertarian themes don’t get made that often.

In my experience, non-liberal cultural critics spend a lot of time complaining about how few works of art, particularly film & television productions, express ideas that align with their worldviews. And they’re right. Most producers and artists in Hollywood don’t really like many ideas that fall outside the narrow confines of cocktail party-progressivism. Movies with conservative or even libertarian themes don’t get made that often.But the solution to that problem isn’t to put on ideological blinders and trumpet any mediocre movie that says something you vaguely agree with, hoping that you can trick a bunch of people into spending their money on a film that says what you want them to hear even though it isn’t any good.

That’s little more than affirmative action for movie reviews, isn’t it?

If you care about seeing your preferred ideas expressed in mainstream culture, then you need to demand that the delivery mechanisms, like movies and television shows, are produced at the highest standards. It’s time to stop grading on a curve.

After seeing the film, however, I was tremendously disappointed. My suspension of disbelief was thoroughly destroyed early in the film and simply never returned. Consequently, I spent the baffling majority of the film wondering why things were happening on screen. It’s really hard to enjoy a cinematic experience when you are shaking your head with incredulity the entire movie.

After seeing the film, however, I was tremendously disappointed. My suspension of disbelief was thoroughly destroyed early in the film and simply never returned. Consequently, I spent the baffling majority of the film wondering why things were happening on screen. It’s really hard to enjoy a cinematic experience when you are shaking your head with incredulity the entire movie. Great stories can have the most fantastical spaceships, amazing technology, superhuman abilities and magical powers, impressive landscapes and strange alien beasts. They can – and perhaps should - completely abandon anything known to mankind.

Great stories can have the most fantastical spaceships, amazing technology, superhuman abilities and magical powers, impressive landscapes and strange alien beasts. They can – and perhaps should - completely abandon anything known to mankind.

One determined young man named Curtis (

One determined young man named Curtis ( I will force myself to stop at this point, as there are many more twists revealed within the final act. However, with all the aforementioned criticisms about a one-sided viewpoint being driven throughout the storyline of fairness and equality, the film is quite an experience in itself and it uses a lot of symbolism for life and redemption. As films go, it has a solid story and extremely well-written characters. Of course, the ensemble cast never ceases to entertain amidst the 2-hour-plus runtime. I never once found myself wondering when it would end.

I will force myself to stop at this point, as there are many more twists revealed within the final act. However, with all the aforementioned criticisms about a one-sided viewpoint being driven throughout the storyline of fairness and equality, the film is quite an experience in itself and it uses a lot of symbolism for life and redemption. As films go, it has a solid story and extremely well-written characters. Of course, the ensemble cast never ceases to entertain amidst the 2-hour-plus runtime. I never once found myself wondering when it would end.